Suggest a trip to Hebden Bridge this weekend and the only problem you’re likely to encounter is finding a place to park. Part of the attraction is the amazing range of independent, specialist shops which won the town top spot in a list of least-cloned towns in Britain.

Another reason is Hebden Bridge’s undeniably off-beat residents. This harks back to when property prices were low and hippy-ish people came here to settle from all over the country. The rich creative life they have established in the town saw it acclaimed in British Airways Inflight magazine as “fourth funkiest town in the world” – top in Europe.

Yet things weren’t always like this.

If you’d suggested that trip to Hebden Bridge four decades ago, the chances are that people would have thought you were barmy.

The town then was more dead than dying, young people left as a matter of routine, the houses were becoming derelict and the mills had already beaten them to it.

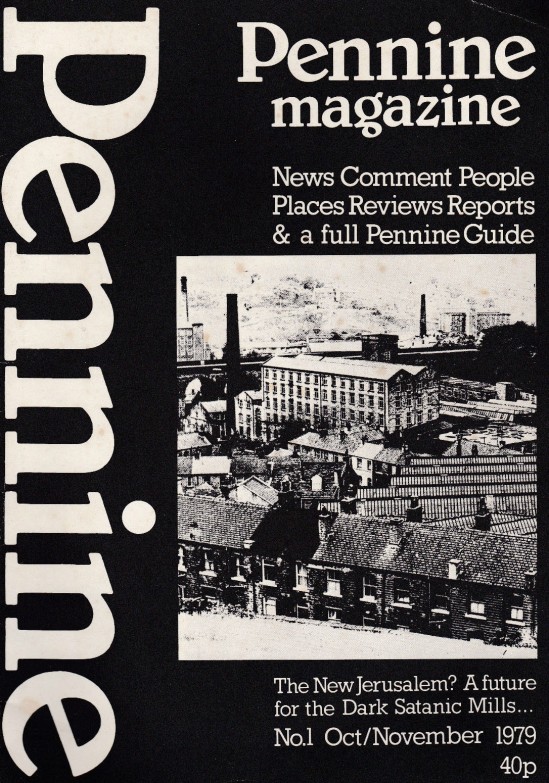

In a room in a former Baptist chapel, in summer 1979, a group of people were determined to change this. Indeed, they had already begun that process and what they were debating now was the launching of a magazine that would help change people’s attitudes and promote regeneration; not just in Hebden Bridge but across the whole of the South Pennines.

The group was the conservationist charity Pennine Heritage, and prominent among its members were David Fletcher and David Ellis, then polytechnic lecturers, and accountant David Shutt, now ennobled and a Liberal Democrat whip in the House of Lords.

The magazine was called Pennine and its famously black and white pages would be adorned by such luminaries as Alan Bennett, novelist Glyn Hughes, Austin Mitchell, Bernard Ingham (then Margaret Thatcher’s right-hand man), photographer Martin Parr and even, by way of a rarely granted interview, JB Priestley.

Richard Catlow was very much a junior member of the group, but as the only person with journalistic experience – a newly-qualified reporter on a local paper – became editor. There were no paid staff or contributors and even the mighty Mr Bennett received exactly the same as the editor – nothing.

In October, with minimal promotion and even less money, the magazine launched in the same week that billionaire financier Sir James Goldsmith brought out the first issue of his Now magazine – it was to be the British equivalent of America’s Time – backed by plenty of both.

One magazine quickly folded, the other went on, boosted by word-of-mouth and a loyal and growing band of contributors, to achieve more than respectable sales, a sort of cult status (just go to a book fair and there’s always someone selling back issues) and, most importantly I believe, to help build a new South Pennine region

After three years the following editorial appeared, which sums up perfectly what the magazine was all about.

It’s Pennine’s third birthday and the pangs of birth (it was rather a painful delivery) and the triumphs of learning to crawl, then walk and even occasionally run, are behind us.

Three’s not much of an age perhaps, but it’s time enough to put the past into some sort of perspective. It seems right to remind our long-standing readers just how Pennine came about, how it comes out and, indeed, why it appeared at all, and to let our newer readers, who must have guessed there’s something a little different about this publication, know just what this difference is.

First came conception in some darkened room, I forget where now. People who had come together in the Pennine Park Association and other voluntary groups thought a magazine could put across their message.

Put simply, the message was — and IS — that the central Pennines with its gritstone hills and textile towns is more than just a sandwich filling between the limestone slices of the Yorkshire Dales and the Peak District.

We live and work here because we like it — not because we have to. We enjoy being here. Where else can you be within walking distance of wilderness and bustling town centres? Where else has such a wealth of history, unappreciated though it may have been?

It seemed fairly obvious to us that places like Huddersfield and Halifax, Burnley and Oldham had a lot in common — they shared the same problems and the same opportunities. But people on each side of the Pennines were going about their business in virtual ignorance of what was happening just a few miles over the hill.

The Pennines might no longer be a barrier to travel, but as far as the spread of information was concerned they were a veritable Iron Curtain. On the Lancashire side you watch Look North West and Granada Reports from Manchester. It’s Look North and Calendar for Yorkshire folk.

Radio stations go up to the Pennine watershed and then stop dead. The national newspapers editionise on a Lancashire and Yorkshire basis. The local newspapers are what they say — local and other magazines are firmly based on their counties.

That’s where Pennine came in.

But it’s one thing to have a bright idea. It’s quite another to put it into practice.

There we were, sat round the table with no money and no experience of running magazines. There was no-one who had ever sold an advert, no-one who knew how you went about circulating a magazine and no-one who had much of a clue about printing.

The money came with a loan from the Joseph Rowntree Social Service Trust, the knowledge from reading, asking and by simply going ahead and finding out. Any expert would tell you it was a recipe for disaster — but we’re still here and more people buy every issue that we produce.

We got offices, we got a secretary who has been run off her feet, but, for almost everyone else, producing Pennine has been an unpaid part-time job on top of doing a full-time job elsewhere or the equally time-consuming task of bringing up young children.

People ring up asking to speak to the editor or one of the reporters, or wondering if we can send a photographer round to see them that afternoon. After the initial shock of being told none are there, most people adapt quite happily to being interviewed at evenings or some odd hour at weekend.

Many even enter into the spirit and offer to take photographs themselves or suggest someone they know who would be willing to compile the article. It not only works— it works very well. People are getting the idea that Pennine isn’t something which belongs to a few of us and which you can read, but something which belongs to all who live in or care about the Pennines.

When the first unsolicited articles began to arrive it was almost a matter of drawing straws to decide who was to tell these folk that we were happy (if the article was good enough) to print it, but that we wouldn’t be paying them anything.

The letters went out. We waited, baited breath. Then the answers came. Almost all of them said “use my article by all means” or something of that sort.

And so it has gone on. Every article that has ever appeared in Pennine — and among the writers have been famous names from every walk of life and some of the best writers in the business — has been contributed freely. The same goes with the photographs.

Still, there’s not many publications where everyone gets the same rate as the editor!

You might think a set-up like this would lead to amateurishness in the worst sense of that word. But we’ve found that people willing to do something for nothing are often of the highest possible calibre.

Now we’re coming to a stage where rising sales means the old free-wheelin’ days could come to an end. But I fancy we might lose more than we’d gain by that course.

Time alone will tell. But I wouldn’t be surprised if things stay much the same and in three years from now we had salesfigures that would be envied by anyone and a wage bill they just wouldn’t believe!

I have about 20 copies of Pennine magazine dated 1984 to 1990. Are they of any value to anyone or should I put them in the green bin for recycling ?

LikeLike